Latest News

- Legendary Mask Maker, Zagone Studios, Approaches Fifty-Years Of Innovation Right Here In Chicago

- Slipknot’s Clown, Shawn Crahan, Is Building A Minecraft World For Gamers With A Theme Of Off Kilter Realm Of Danger And Mayhem

- Photo Gallery: Bobby Rush @ Buddy Guys Legends

- Photo Gallery: Buddy Guy @ Buddy Guys’s Legends

- The Blues Don’t Retire As Buddy Guy’s January Reign at Legends Continues To Sell Out And Amaze

- Red Hot Chili Pepper Bassist, Flea, Releases Debut Solo Album And Embark On First Ever Solo Tour With Opening Night At Thalia Hall

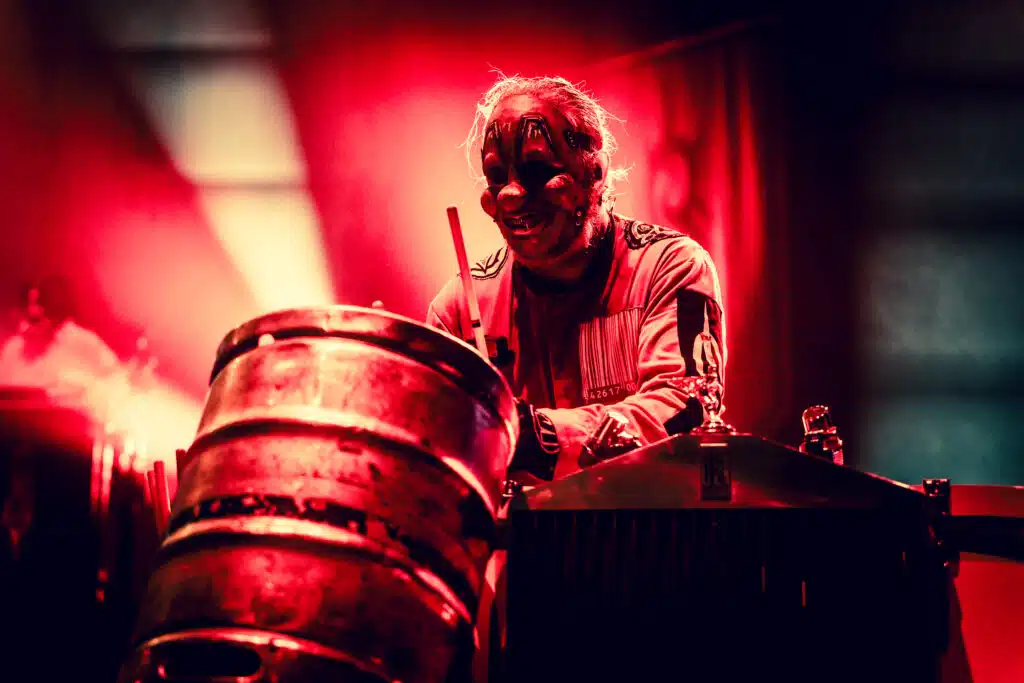

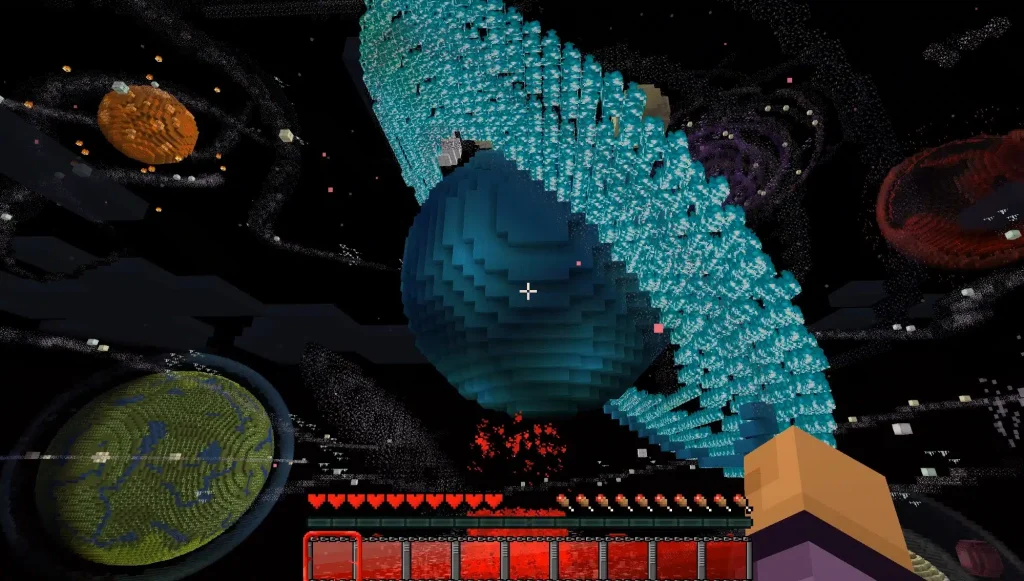

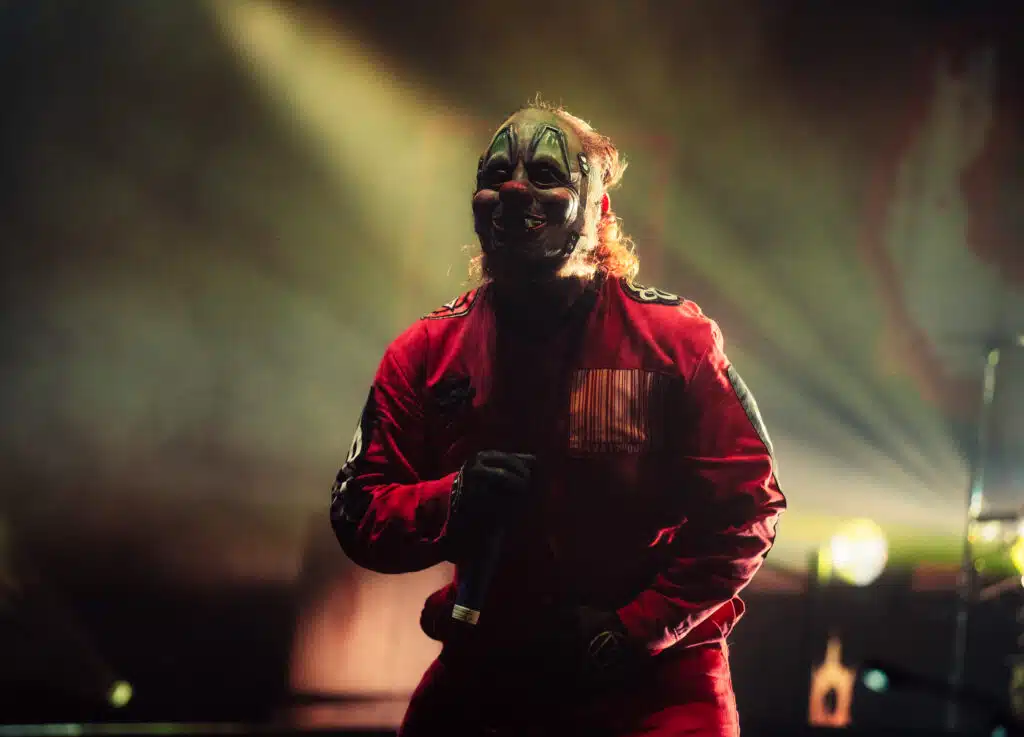

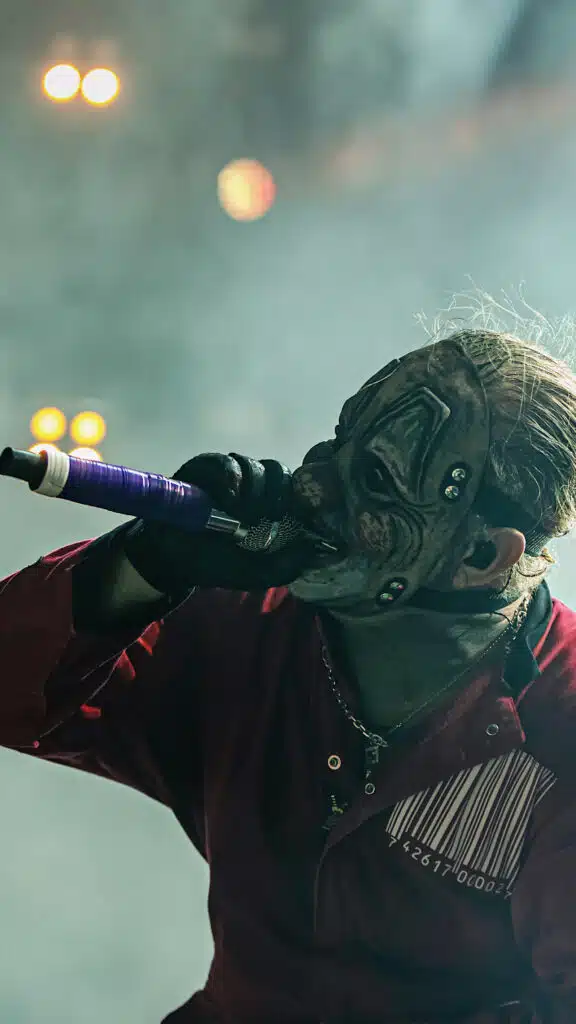

Slipknot’s Clown, Shawn Crahan, Is Building A Minecraft World For Gamers With A Theme Of Off Kilter Realm Of Danger And Mayhem

Jan 17, 2026 admin_bitlc Features, Music News, Reviews 0

In an article from The Escapist, Crahan goes into details about why he’s creating this art experiment, what it means and where it’s going.

From Paul McNally:

Shawn “Clown” Crahan doesn’t talk about games like a celebrity who’s been handed a controller for a photo op. The Slipknot founding member talks like someone who’s spent decades living in the overlap between art and obsession, the kind of person who sees a digital world less as “content” and more as an engine for coping, creating, and connecting.

“I’m 56 years old,” he tells me when we meet, and when he says he was “there when I lost my best friend to video games,” it isn’t a moral panic. It’s the opposite: a marker of the moment his generation tilted from woods-and-bikes childhoods into screens and systems. Back in late-70s/early-80s Iowa, games arrived like portals. “My best friend had Atari. I had Intellivision,” he says, brightening immediately, and if you grew up the same way, you can hear the grin in it. “Intellivision was the best.” My ears had pricked up at that, as I was also team Intellivision against the wave of Atari kids.

Clown’s gaming DNA is part tabletop too. He grew up around the kind of board games “that make Risk look like nothing,” and around role-playing. “My best friend played D&D,” he says, but he always felt more physically wired, less muscle-memory grind, more sensation, more discovery, more what happens if I do this?

That question, what happens if I do this?, is basically the thesis statement for Vernearth, the Minecraft realm he’s been building into a full-on art project. It’s also why, when he talks about the modern games industry, he doesn’t sound nostalgic so much as disappointed.

“I’ve been around the corporate world my whole life,” he says. “There’s nothing wrong with the corporate world, but it ends up being a bunch of nerds and people that just don’t want to look at it another way.” When he says “nerds,” he clarifies he doesn’t mean it as an insult, more as tunnel vision. “There’s no room for the error. There’s no room for the glitch. There’s no room for the exploring.”

He grew up wanting secret rooms. He grew up loving the ugly magic of early arcade weirdness, when breaking the rules wasn’t a scandal, it was the point. “I grew up on Donkey Kong arcade games where you’d take the player and throw him over on the side in the air while the barrels rolled down… that was a glitch. So I grew up on glitches and weird manufacturing.”

And now, at the end of 2025, he thinks the industry’s terror of that kind of chaos is going to cost it. “It’s very transparent that everyone just copy-copy” he says, and then he shrugs it off with the sort of cold confidence only someone with decades of survival-bred success behind him can deliver: “It’s good though, because they’ll all fail. They’ll all lose all those millions of money from copying each other… that’s not what life is.”

He isn’t doing Vernearth because he wants to make a safer Minecraft. He’s doing it because he wants to make a stranger one.

From Quake to Goat Simulator: why absurdity matters

Clown’s tastes track a certain lineage: games as systems you can bend, worlds you can alter, places where the player isn’t just completing tasks but testing reality. “Once I got onto Wolfenstein, it took me to Doom, which took me to Doom 2,” he says, “when Quake hit, it revolutionized my brain.”

For him, Quake wasn’t just a shooter it was a cultural event because it opened a door. “Quake released OpenGL to the public to go ahead and have fun,” he says, and he remembers thinking he’d “gone to heaven.” Because for someone wired like Crahan, the thrill isn’t just aiming. It’s possibility.

He tells a story that perfectly explains his fascination with player ingenuity: modders taking the code for a Rottweiler enemy and swapping it into the grenade launcher so the gun fired dogs instead of explosives. “I would get the grenade launcher, I would get the ammo of Rottweiler, and I’d unload seven or eight Rottweilers at my best friend,” he laughs, marvelling less at the kill and more at the idea that somebody even thought to do it. “I don’t even care that he’s dying. I’m like, can you believe this?”

That’s his lens: games as a living culture, not a fixed product.

And it’s why he rates something like Goat Simulator so highly. He calls it “so ridiculous and so out of control that you almost can’t find yourself in it, but when you do, it becomes this epiphany of potential.” The absurdity is a feature, not a bug. He says it is like a Sharknado movie, proof that someone, somewhere, still has the balls to make something with no shame and no safety rails. “People want crazy out-of-the-box thinking to stay loose in this reality.”

Minecraft, grief, and why Vernearth exists

He speaks about Minecraft with something close to reverence. “I come from nothing but respect and love for the genius of Minecraft,” he says, and it’s not a band-guy talking point. It’s parental memory: “I have four children who grew up on it… I was in the mall and bought Minecraft the first day it was released. I’ve watched all the updates.”

His kids didn’t just play it; they revealed it. “All four of my kids are different,” he says. “Some of them liked redstone, some of them didn’t. Some liked color palettes, the other ones couldn’t care less.” Minecraft, to him, is the rare platform that doesn’t demand one type of brain. It accepts them all.

Then he says it plainly, and the tone changes: “Unfortunately, we had lost a child.”

He doesn’t turn the conversation into spectacle, and neither will I. But he’s direct about how this feeds into what he’s building. When grief happened, he went looking for ways to survive it, and Minecraft became one of them. “I was finding many avenues to help me grieve in the way that I need to,” he says, and long story short, it led to him looking at Minecraft “fundamentally,” not just as a game but as a framework.

“I’m not using it because it’s the biggest game ever,” he says. “The potential of it, because of coding and utility, it’s sort of like a giant cracked-out OpenGL situation for me.”

That’s Vernearth in one sentence: Minecraft as a living OpenGL playground, turned into an art project that can hold emotion.

He describes last night’s session like it’s the most normal thing in the world: dozens of people online, five or six building closely with him, collaborating, altering each other’s work without ego. “They were letting me build and then they were helping me,” he says. “I was warming them up to the idea: you can change any of my stuff, add to it, let’s work together.”

For someone living through heavy thoughts, that kind of co-creation isn’t just “community engagement.” It’s medicine. “If I’m going to live in a dark place and I’m going to grieve and I need to be in my imagination,” he says, “it’s flawless.” A girl on the server mentions she’s in the UK, maybe even in Manchester like me, and he has that small, stunned thought you only get when life suddenly feels impossibly big and strangely intimate at the same time: “This is everything I ever dreamt about.”

Then he lays out the origin story like a myth: “Shawn Crahan, the Clown… bought his own server, employed the engine of Minecraft onto it, uploaded it, started bringing builds I’ve been doing for years, and brought in a whole team of people that can think like myself.” The result: “And then I created a world. It’s called Vernearth.”

In Vernearth, he explains, “Vernearth is the solar world… and the Oblivion is where you’re walking around.” But what makes it different isn’t just the lore, it’s his impulse to treat Minecraft’s building blocks like raw materials. “I get to look at the block,” he says, “and I get to change it. I get to make utility.”

He’s building his own biomes, his own blocks, his own mobs, “my own NPCs, my own sky,” coded in a way that he insists is collaborative rather than parasitic. “I choose to live hand-in-hand with the platform,” he says. “I’m not trying to turn it on its back. I’m trying to be an option.”

And crucially, he says the payoff isn’t cash. “I’m utilizing the things I love for major reward that isn’t monetary. It’s purely spiritual.”

That line matters, because Crahan’s idea of Vernearth is less “Slipknot Minecraft server” and more “the biggest art piece I’ve made in my entire life.” Not because it’s massive, but because it lets him combine everything. “It obtains music. Scoring and music. It obtains coding, utility, vision,” he says. “It’s right in my own culture… it’s like a meet and greet, but instead of you go, I get to hang out with you all night and build a tunnel.”

It’s the most Clown sentence imaginable: a meet-and-greet where you build a tunnel.

Even on tour with Slipknot Vernearth doesn’t get paused, it just gets squeezed into the margins between chaos and showtime. Crahan tells me “I’m known to literally have my stuff on while I’m making things and be told it’s time and go. Not because he’s trying to be some tortured workaholic, but because creating is how he carries the weight without dumping it on the people around him. “I got a lot on my mind, man… and I don’t want to dump that on my wife… I don’t want to dump that on the fans… I want to love.”

“I try to recreate creation”: Clown’s world is designed to be broken

A lot of creators talk about community, then quietly panic when the community behaves like… people. Crahan seems to crave it.

He starts telling me about a Slipknot-branded block, a tribal S design, with variants handed out by different members of the team, and how immediately the community did what communities do: they stole them off each other. “Every time we give them away, everybody’s stealing them,” he says, and rather than sounding angry, he sounds delighted by the sociology of it.

The theft forced structure. Community guidelines, accountability systems, rules you can actually enforce.

At one point, he says people were “talking about making their own government so they could shake people out,” and Crahan’s reaction is basically: yes. Good. That’s the point. “Here we go,” he laughs. “This is everything I wanted.”

That’s his creative stance across the whole project: let them break it. Let them glitch it. Let them reveal the edges so the edges can evolve.

He’s obsessed with farms for that same reason. “Farms end up being my favorite thing in Minecraft,” he says, fascinated by the way players “capture the automation and make it work for yourself when you’re sleeping.” He loves that people copy the same farm, then refine it, then obsess over “the mathematics and the ticking” behind Minecraft’s systems. He’s drawn to the mind that stares at a sandbox and sees a spreadsheet.

Then he does what any good systems designer does: he adds variables.

Crahan talks about a custom vampire mob his team created, and the idea that players are already discussing how to build a vampire farm, something he’s never seen before. The drop rates are intentionally rare: “one out of 10,000” type logic, designed to create a new kind of long-term pursuit that doesn’t exist in vanilla Minecraft.

He’s also candid about the danger of that approach: the devs don’t even know what players are doing with it yet. “We don’t know if they’re going to get a pet every hour and we have to redo it,” he says. “It makes it glitchy… we don’t even know what they’re doing and we don’t know how they’re doing it yet.”

And then he basically summarises his entire design philosophy in one moment: “Look at this dude. He’s duplicating rail. We’ll have to shut it down, of course, but I’ll be like, ‘Bravo, bro.’”

That is Clown in a nutshell: fix the exploit, celebrate the mind that found it.

“We are on our way out”: stop trying to force kids to be us

The interview takes a turn when we start talking about kids, screens, and attention spans, the modern parental anxiety bundle. I mention how my own kids won’t read books; everything is iPad, everything is ten seconds long, and it’s hard not to feel like something’s been lost.

Crahan doesn’t sugarcoat it. “Unfortunately, my friend… there’s nothing you can do,” he says. Not because he’s given up, but because he sees the machinery. “The god corporate hand of money has way too much money to brainwash everybody and everything around us.”

Then he shifts to something sharper, something a lot of people don’t want to hear, especially if they’re over fifty.

“You and I… we are past 50 years old. We are on our way out. It’s guaranteed,” he says. “These kids are coming up. So it’s not our right to sit there and go, ‘Damn, you don’t read a book. Damn, you don’t do this.’”

Instead, he argues for influence without control: show your kids what you love, and let them decide whether it sticks. “Find those things that actually interest you and figure out a way to show that to at least your children,” he says. “Hopefully because of their love and admiration for you… they might take a liking to it because their dad does.”

But he does draw a line around language, books, and attention. “Reading a book, that’s very important,” he says, and he frames it as cultural preservation rather than morality. “Every day they change the words in those books. Words are going away… it’s our duty to make sure we don’t lose words, we don’t lose colors, we don’t lose the ability to not be on the phone.”

His practical solution is wonderfully blunt: social boundaries. “If I’m going to dinner, I tell people to leave the fucking phones in the car,” he says, because he refuses to pay for a meal where everyone’s somewhere else. And then he admits the grim truth anyway: “The minute everybody gets to their phone, including myself, we’re right back on it. We are stuck.”

So he returns to the only thing he thinks we can honestly do: create while we can. “You and I… we can still write books. We can still manipulate video games. We can still give art and color, taste, smell, feelings, emotions,” he says. “We can only contribute while we contribute.”

And that’s where Vernearth becomes more than a realm. It becomes his answer to the present tense. “I try to recreate creation,” he says. “To reimagine imagination.” In Vernearth, he wants to prove that someone who seems untouchable is “touchable,” not as a brand, but as a person who’ll build something “flowery and Hallmarky” with strangers at midnight, like a platform where players can get married, or celebrate an anniversary. “The culture was helping me,” he says, “because that’s what we wanted to do.”

He isn’t trying to alter the future. “I’m just going to live in the present, take from the past, and hopefully create something that lasts,” he says, and when he adds, “when I’m gone, hopefully Vernearth will be standing strong,” it lands like a mission statement.

The slow grind: auction houses, plot worlds, and the nightmare of in-game money

For all the talk of imagination and spirit, Crahan is deep in the practical trenches too, the stuff most people don’t see when they imagine a famous artist “making a server.”

He’s months behind, he says, because the idea was too big at first. “We started all of it at once,” he explains, “and then we had to slow the whole thing down and start on certain things.” One of the biggest headaches has been in-game money, because the moment you touch real-world transactions, you inherit a world of banks, taxes, and friction. “Uncle Sam wants his,” he says dryly, “and banks don’t necessarily understand in-game money.”

He laughs that he doesn’t even know why he wanted that system, and then immediately confesses he knows exactly why: “I love the auction house in World of Warcraft.”

It’s not just about trading. It’s about theatre. “You go there and just watch everybody in their outfits and their mounts,” he says. It’s a social hub. “The auction house brings all of the community together in one area… because you could be underground and never see this guy as long as you live. So this brings people out.”

He’s also building what he calls a Plot World, a protected showcase space where players can display builds that can’t be broken or stolen. “You’ll get a 52 by 52 block plot,” he explains, and whether you copy a build from the Oblivion or rebuild it from scratch, the point is preservation: admiration without grief.

It’s Minecraft, but with safeguards built around community behaviour, the same way any society ends up building guardrails once it realises people will absolutely nick the tribal S block the second you turn your back.

“AI is a professor in my pocket”: Clown’s take on the tool everyone’s panicking about

Near the end, I ask him about AI, whether it scares him, whether it’s going to ruin everything, especially since he co-habits two industries AI is actively chewing on: music and games.

Crahan’s answer is not what the internet wants. He doesn’t play the outrage hits. He doesn’t do the “it’s the end of art” sermon. He says, flatly: “I’m employing AI 190%.”

Then he reframes the entire debate as something simpler: intent. “I’ve been using AI my whole life,” he says, referring beyond this current wave of tools, but the broader reality of technology as assistance. “No one needs to use it,” he adds, acknowledging the purist position. But for him, AI isn’t an artist. It’s a helper.

“The way I look at it,” he says, “it is a professor in my pocket who only wants to do what I ask it. Its only job is to make me happy, me, not you, not the world, no one.”

He gives a practical example: poetry. He has “thousands and thousands” of poems he’s written since he was young. With AI, he can feed it his own words and ask for transformations without surrendering authorship. “Here are my words,” he says. “Don’t change them. Don’t alter them. But show me some different ways to sing it.”

And then he delivers the point with the blunt clarity of a man who’s booked studio time his whole life: what’s the difference between that and chasing a high-end producer? “What’s the difference between me pulling out my pocket producer… or me trying to get a famous producer that might not even work with me and could potentially cost me $150,000… who will only give me one or two ways – I’m not mentioning any names!”

Either way, he still has to perform it. “It’s still going to take me to sing it,” he says. “And it will never be like it was.”

He doesn’t ignore the danger. He tells a story about someone feeding a family tragedy into an AI system and getting a reckless, accusatory response back. “That’s pure insanity,” he says. “I would tell the person: get out of there. What are you doing? That’s dumb.” His issue isn’t with the tool existing; it’s with humans using it badly.

And that loops back to his central claim: the tool doesn’t act alone. “None of it can work without you, the human,” he says. “It’s a giant oracle… but it needs you.”

Crahan is also realistic about the generational disconnect. “Our generation is going to hem and haw about AI,” he says, and then he asks the question that answers itself: “Do you think some kid in fourth grade who’s grown up on it agrees with you and I about how horrible AI is? This is the implemented tool of life today.”

He doesn’t believe you can stop it. “You and I will never have enough money or power to sway anybody away from what life is doing,” he says. “Life is moving forward. And AI is part of it.”

Then he throws the heaviest punch of the whole section: “AI is the least of our worries on this planet. We currently are the worst of our worries and have always been the worst of our worries.”

So for him, the only coherent position is tolerance in both directions: it’s fine not to use it, and it’s fine to use it, but don’t pretend it’s going away. “Always dig within your own self to prove you can do anything,” he says, encouraging artists to build their fundamentals first. And then, almost softly, he adds the part that will annoy the doomers most: “There’s a lot of love in AI. There just really is. It’s a beautiful thing, in my opinion.”

Vernearth as an art project you can actually step into

Crahan talks about Vernearth like someone building a place he intends to live in, not a product. He wants to work “hand in hand” with Minecraft one day, not because he wants legitimacy, but because he wants resources: “My dream is that Minecraft might call one day and say, ‘What do you want to do now?’… because I can’t necessarily afford the team I need to make my fullest ideas come true.”

Until then, it’s the slow grind, reinventing the Nether, reinventing the End, adding factions where you “pick a side” without a clean good-or-bad binary, shaping PvP, Plot World, and other systems he’s not ready to reveal yet. And he sounds genuinely excited to log back in the second our call ends. “It’s absolutely doing what I wanted to do,” he says. “It’s community first and foremost… it’s wonderful.”

If you strip away the Slipknot mythology, what’s left is the more interesting story: a lifelong creative who grew up chasing secret rooms and loving glitches, now building a realm where the glitch is still holy, not because it’s broken, but because it’s the most human of all.

And if you’re wondering why The Escapist is talking to a metal icon about Minecraft, Crahan answers that too without even trying: he’s not building Vernearth to relive the past. He’s building it because the present is heavy, the future is coming anyway, and creating something with other people, something you can “taste and smell,” something that holds art and community and grief in the same blocky hands, is the closest thing he’s found to staying alive inside it.

- Clown, Minecraft, Shawn Crahan, Slipknot, Vernearth, video game creation, video game design, Video Games

Related Articles

-

Photo Gallery: Puddles Pity Party live...

Photo Gallery: Puddles Pity Party live...Sep 25, 2025 0

-

Flashback Friday: Slipknot @ Congress...

Flashback Friday: Slipknot @ Congress...Aug 22, 2025 0

-

The Life And Times Of A Metal Giant And...

The Life And Times Of A Metal Giant And...Apr 26, 2025 0

-

A Teens Perspective: C2E2 Returns For...

A Teens Perspective: C2E2 Returns For...Apr 13, 2025 0

More in this category

-

The Blues Don’t Retire As Buddy...

The Blues Don’t Retire As Buddy...Jan 16, 2026 0

-

Red Hot Chili Pepper Bassist, Flea,...

Red Hot Chili Pepper Bassist, Flea,...Jan 14, 2026 0

-

Chicago Country Music Festival Windy...

Chicago Country Music Festival Windy...Jan 13, 2026 0

-

Swedish Artist, José González,...

Swedish Artist, José González,...Jan 13, 2026 0